We are honoured to welcome our good friend Emily Russell, to talk about her grandmother Maud Russell, whose diaries Emily has recently edited for The Dovecote Press. Maud Russell has hitherto only been a footnote in the story of Ian Fleming, but as her diaries demonstrate, was a far more important figure in Fleming’s life than previously understood. We spoke with her at the launch of the book at the beautiful Mottisfont Abbey near Romsey in Hampshire, where Maud lived for much of her life.

Why did you decide to compile Maud’s diaries into a book?

It was something my father, Maud’s son, spoke about when he was alive. We didn’t have access to the diaries at the time but he always felt that she’d lived such an interesting life and the diaries would provide the material for a good biography. When I began reading her diaries, it struck me how many fascinating entries were packed into the war years. I thought ‘Why write a biography when she can tell her own story so eloquently herself with the backdrop of the Second World War’?

Maud Russell’s War Diaries (Photo courtesy of Emily Russell)

Maud Russell (Cecil Beaton photo: courtesy Sothebys, London)

My grandmother was an unassuming person who didn’t blow her own trumpet. This meant that her story was mostly untold. By publishing her diaries, I saw an opportunity to provide a fuller picture of her and at the same time correct a few misunderstandings about her. For example, biographers of Rex Whistler have given her a bad press for her treatment of Whistler when he decorated the room at Mottisfont. A Constant Heart tells her side of the story for the first time and, I think, sheds quite a different light on their relationship and the Mottisfont commission.

Was Maud specifically interested in the trompe l’oeil style of art or because of her friendship with Rex Whistler?

My grandmother wanted a gothic architectural treatment for the room that would reflect the house’s medieval origins as an Augustinian priory. She specifically envisaged grisaille painting – painting in a grey or neutral tone often used to imitate sculpture. She would have known that Whistler had the technique and imagination to transform this idea into a glorious reality, otherwise she would not have commissioned him. By using trompe l’oeil, Whistler was able to create the appearance of gothic pillars and vaulted ceilings to spectacular effect in the room.

The Whistler Room: © National Trust images / Andreas von Einsiedel

Rex Whistler’s trompe l’oeil ‘smoking urn’. A joke since Maud hated bonfires. (© National Trust images)

Maud’s relationship with Ian seemed very close in many different ways, typically meeting over a lunch or dinner. A pivotal moment in Fleming’s life was when his love Muriel Wright died in the Blitz. Maud consoled him at her flat on 39 Upper Grosvenor Street. For Fleming fans, new information as a result of your book will be a boon. Were you aware of how important this connection was growing up?

Not at all. Fleming was just one of the many politicians, artists or writers that were talked about as having stayed at Mottisfont. I had no idea how close they were. It was only when Andrew Lycett’s biography was published in the mid-90s that I heard they were said to have been lovers. But reading the diaries I gained the impression of a much deeper, more intimate friendship that lasted 20 years until his marriage to Ann Charteris, when they began to see each much less.

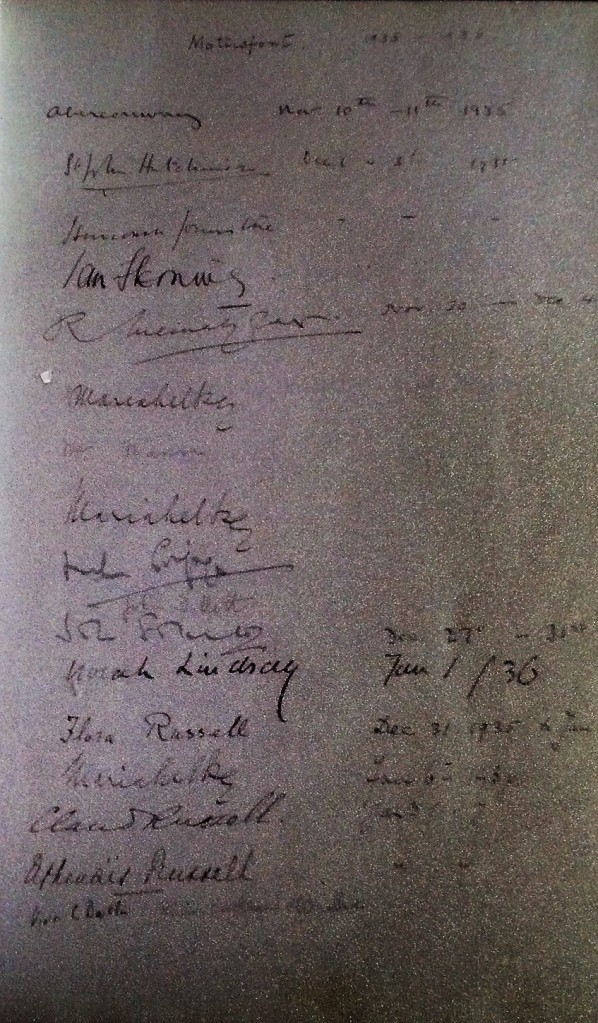

The Mottisfont Visitor’s Book with Ian Fleming’s signature, 1935 (photo: literary007.com)

It was very touching to find out how much they cared for one another; Ian giving her advice on family problems and getting her a job at the Admiralty and Maud providing him with an escape from wartime work with dinners at her flat, when they’d fantasize about post-war life, and taking care of his rations for him. The biggest surprise was discovering her gift to him of Goldeneye, his retreat in Jamaica, which had remained a secret for so many years.

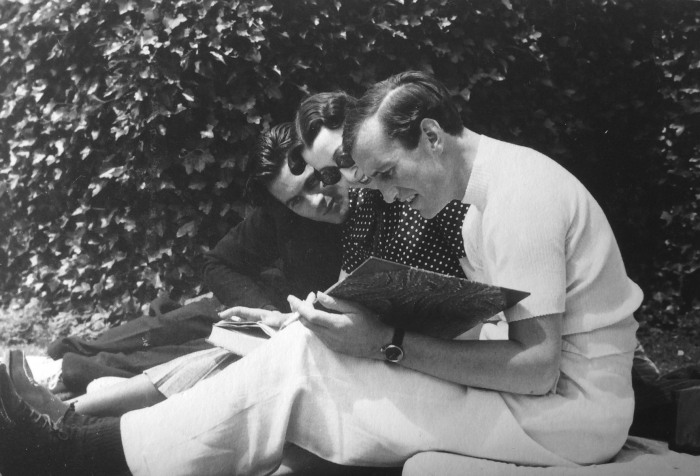

Maud and Ian (credit: the Maud Russell estate)

‘If I wait for genius to come, it just doesn’t arrive’ – Ian Fleming, a regular guest at Mottisfont. (photo: literary007.com)

Maud and your grandfather Gilbert were also pivotal in getting Ian his first banking job at Cull & Co. the merchant bank, of which Gilbert was a partner with Anders Cull, Hugh Micklem and Hermann Marx. Gilbert also appears to have helped introduce military contacts to Ian during parties at Mottisfont Abbey. What sort of a person was Gilbert?

Gilbert died long before I was born but my grandmother always spoke about him with devotion. He was apparently the only man who really made her laugh. Relations talk about him as a kind, caring person and the diaries bear this out with Maud often mentioning his help to family members. On his death, she received over 200 letters of condolence and many of them refer to his wit and good nature. Margot Asquith described him as having a “fine temper, sense of humour and good-fellowship.”

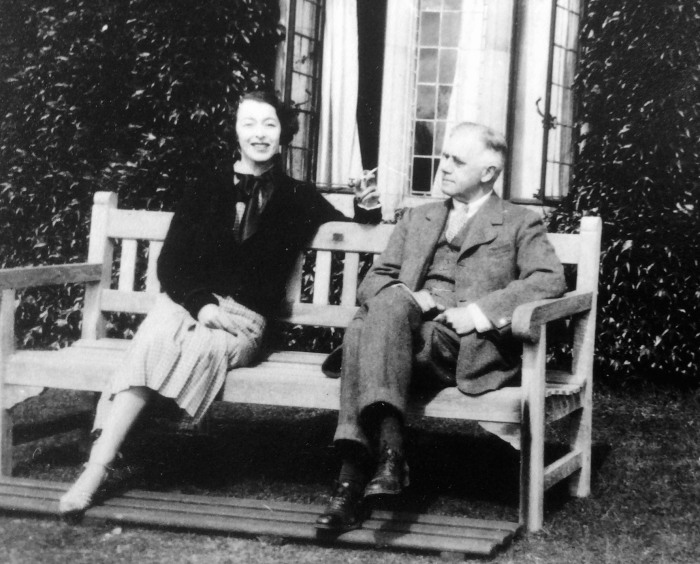

Maud and Gilbert Russell (credit: the Maud Russell estate)

What was it like growing up with Maud and visiting Mottisfont Abbey?

My visits to Mottisfont as a child hold a special place in my heart. We were allowed to run wild on the entire 2,000-acre estate and used to spend the day exploring the woods or walking along the river. In the summer we swam in the Abbey Stream and the Test. We’d always be back for tea, cucumber sandwiches and cake in the Morning Room or under the great Plane tree when the weather was fine. My grandmother was always low-key and kind to me but I still held her in awe. There was a quiet aura around her. An air of culture and intellect pervaded the house. As we grew older she’d take us on at Scrabble and Croquet and always beat us, and would always ask us about ourselves and what we were doing at school.

Mottisfont Abbey: © National Trust images / Robert Morris

Your mother Anne was also part of the war effort, working at Bletchley Park. Can you tell us a little bit about her?

My mother’s father was in the army, she had two older brothers whom she admired and she grew up to be a strong, freethinking woman. She joined Bletchley when she was 17 probably due to her good French – which was spoken at home – and her father’s military background. But bored with the repetitive work at Bletchley, she went on to become an ambulance drive for the Free French, serving in the Alsace campaign in 1944 and crossing the River Rhine with the Allies in 1945. She was a fearless woman with a no-nonsense attitude to life. I would say her main attributes were her deep sense of loyalty and inner strength – interestingly characteristics that she shared with Maud.

Anne Russell meeting American officers (credit: The Daily Telegraph)

What has publishing these diaries meant for you and your grandmother’s legacy, and do you have plans to release any more of her diaries at a future date?

For me, editing my grandmother’s diaries for publication has been a great privilege and an exciting voyage of discovery. She was a private woman and the diaries were full of revelations including her efforts to help her Jewish relatives flee Nazi Germany. So far as her legacy is concerned, I hope the diaries go some way to providing a more complete picture of her rather than the stereotype of a rich, conventional woman that has prevailed in some sources until now.

For me, editing my grandmother’s diaries for publication has been a great privilege and an exciting voyage of discovery. She was a private woman and the diaries were full of revelations including her efforts to help her Jewish relatives flee Nazi Germany. So far as her legacy is concerned, I hope the diaries go some way to providing a more complete picture of her rather than the stereotype of a rich, conventional woman that has prevailed in some sources until now.

The diaries show that she had an insatiable curiosity about life and while discreet, she was far from conventional as her 25-year relationship with the Russian artist Boris Anrep shows. As for the future release of diaries, I’m not sure at this point. There are further stories to be told but I am not yet certain about how.

Incidental Intelligence

Emily Russell is Maud’s granddaughter and has spent the last three years editing and preparing her diaries for publication. She worked for Amnesty International, the Howard League for Penal Reform and the Campaign for Freedom of Information before becoming a journalist and eventually moving to Chile.

Emily Russell is Maud’s granddaughter and has spent the last three years editing and preparing her diaries for publication. She worked for Amnesty International, the Howard League for Penal Reform and the Campaign for Freedom of Information before becoming a journalist and eventually moving to Chile.

Buy ‘A Constant Heart’ on Amazon

‘Maud Russell: mistress of Mottisfont Abbey — and Ian Fleming‘ by Andrew Lycett (The Spectator)

‘Spies, affairs and James Bond… The secret diary of Ian Fleming’s wartime mistress‘

Charming, touching and wonderfully presented. A terrific backstory to Fleming and his relationships with women – especially Maud – and her gift of GoldenEye to Ian had me gobsmacked! Thank you Emily for your dedicated efforts.

Hello, I have recently found out that my great grandmother was the nanny of Maud and Emily Russels german Jewish relatives (Agnes Nelkes children)- we have several pictures of the Family and a Journal. It would be so great to hear from her!

I am the widow of Esra Bennathan who was the grandson of Agnes Nelke. I can be reached at judithnowak@comcast.net