Article by Dannielle Shaw

‘One reads him for literary delight and for the pleasure of meeting an Elizabethan spirit allied to a modern mind’. Vita Sackville-West on Peter Fleming.

The hybrid role of soldier-travellers and traveller-intelligencers has long been a complementary but complex pairing. Peter Fleming was a soldier-writer, a travel-writing soldier, and a serving traveller-intelligencer. The most interesting of men have often had one or two of these titles, but to combine four is truly remarkable.

The hybrid role of soldier-travellers and traveller-intelligencers has long been a complementary but complex pairing. Peter Fleming was a soldier-writer, a travel-writing soldier, and a serving traveller-intelligencer. The most interesting of men have often had one or two of these titles, but to combine four is truly remarkable.

Traditionally, the spy’s coterie has a shared interest and expertise in language, self-reliance, interpersonal skills, military experience, experience abroad, higher education, life experience, and a proficiency for storytelling. Peter Fleming had all of the above, and more. He had connections, and an excellent family background. Educated at Eton and then to Christ Church, Oxford, where he graduated with a first in English – he was both a member of the Oxford University Dramatic Society and of the notorious Bullingdon Club, whose members have included an array of faces later seen tasked with tending to Britain’s political establishment. But this was not to be Peter’s fate. Instead, he became literary editor for The Spectator, but was a rather restless being and in 1932, after eschewing ennui for excitement, Peter embarked on a much-needed adventure by replying to his ‘favourite sort of advertisement’ in the Agony Column of The Times:

Exploring and sporting expedition, under experienced guidance, leaving England June, to explore rivers Central Brazil, if possible ascertain fate Colonel Fawcett; abundance game, big and small; exceptional fishing’ ROOM TWO MORE GUNS; highest references expected and given. – Write Box X, The Times, E.C.4. (p.12 Brazilian Adventure).

Peter deliberated at first, and pretended to himself that it would be too absurd to ‘give up a literary editorship of the most august of weekly journals in favour of a wild-goose chase’, but relented, and wrote off to Box X with a laconic response: Peter Fleming, 24, Eton. Christ Church, Oxford. Ian Fleming, creator of the James Bond series, described his brother, Peter, as a ‘law unto himself’, and as Peter chose to descend into the perilous Conradian backdrop of uncharted jungle and exotic tropical flora and fauna, we can begin to comprehend why Ian might say so.

Photo: The Press Reader

Aspiring to the improbable is what made Peter tick, that, and the hunt. Peter was an excellent marksman and loved shooting, and though the expedition failed – unable to ascertain the fate of Captain Fawcett – he had enough material to produce the best-selling travelogue Brazilian Adventure (1933).

Duff Hart-Davis, Peter’s only biographer to-date, noted that

The expedition as a whole left him outwardly unchanged, but it taught him a good deal about himself – that his powers of leadership, for instance, were considerable, and easily asserted themselves in a crisis; that his physical endurance was equal to anybody’s, and his tolerance of discomfort astonishing. (p.109, Hart-Davis)

But the most important thing that Peter learned on this trip was that he was compelled to seek adventure: he needed to battle danger, and he needed to write about the experience. From this, ‘he found enormous satisfaction and set the pattern of his life for the next few years’. After Brazil, Peter went on to the Far East and Moscow, and it was these adventures, combined with the skills gained in the Brazilian rainforest, that would furnish him with an advantage during the impending war.

Peter had extensive knowledge of the Far East, and was recruited to serve as an intelligence agent for field work and special duties. Peter’s knowledge and experience was so in demand that he was recruited an entire month before the Second World War was officially declared. His position in intelligence, would take him all over the globe – to Norway, Africa, Egypt, Greece, India, and China. Subsequently, Peter went on to work in strategic deception, something his brother Ian would later find himself doing for British disinformation strategies, such as Operation Mincemeat in 1943.

Whilst Peter is often referred to as one of the blueprints for Bond, it is important to understand that he was so much more than that. He was a best-selling author, a journalist, an adventurer, a travel writer, the husband of an Oscar-award-winning actress Celia Johnson (of Brief Encounter fame), a squire of his country estate in Nettlebed, father to three children, and an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. Ian believed Peter ‘seemed so perfect’ growing up (p.7, Lycett), and from reading the illustrious list of aforementioned achievements, one can see why.

Though Peter acknowledged that the brothers ‘fought like cat and dog’, he maintained that they were close. Ian, however, perhaps understandably, felt like he was a pale imitation of his more successful, more distinguished older brother. In The Letters of Ann Fleming, Mark Amory, Ann’s literary executor and family friend, Amory remarks that,

He [Ian] was not however as classically handsome as his elder brother Peter; nor was he as clever, popular, rich, serious, or virtuous. Ian had grown up in the shadow of just about the most promising young man in the country and one on whom the elder generation beamed approval. (p. 35, Amory)

Ian lacked the academic capabilities that came so easily to Peter. And Peter’s formative years were not marred by scandals like Ian’s had been. There was only a year between them, but Peter often led the way with occupations and endeavours that Ian himself would later engage with. For example, Ian acquired his position in intelligence five months after Peter had first secured his.

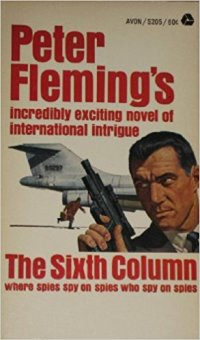

Similarly, Peter wrote The Sixth Column (1952), an espionage-themed novel which satires the bureaucratization of the secret services, which he dedicates to Ian, an entire year before Casino Royale was published. Many marvel at how quickly Ian produced his novels, but with his brother forever pipping him to the post perhaps this gave Ian further incentive and fuel for the fire. It was at Peter’s behest that his first publishers, Jonathan Cape, were also to – rather reluctantly – become Ian’s. Ian continued to use Jonathan Cape for his famed espionage series for the rest of his life. He also used them when publishing his own well-humoured travelogue, Thrilling Cities (1963). Both brothers shared a deep passion for adventure, travel, and writing: the hybrid role of the traveller-intelligencer is a shared leitmotif in the Fleming brothers’ catalogue.

The influence Peter had over his brother has often been discussed by biographers of Ian Fleming including John Pearson, Andrew Lycett, and most recently by Robert Harling. Both born in May, almost a year apart with Peter on the 31st and Ian on the 28th. Peter, rather prematurely, became the man of the house at an early age when his father, the MP Valentine Fleming, a close friend of Winston Churchill, was killed in action by German bombs in Picardy, in 1917. Peter, in his own words, recalled the day that Evelyn Fleming received the telegram relaying Val’s death, and remembers being told ‘you must be very good and brave, Peter, and always help your mother: because now you must take your father’s place.’ Those words rang out for Peter, who acknowledged them and absorbed them instinctively.

Throughout his life, Peter continued to give his unwavering support to his family. Peter was always there for Ian, and took a special interest in his writing career; carefully editing, proofreading, and suggesting changes to character’s names, including Miss Moneypenny. Peter also continued to support Ann and Caspar, Ian’s wife and only child, after Ian’s death. In a letter to Evelyn Waugh, Ann Fleming discusses dealing with the solicitors after Peter’s mother’s death (Evelyn Fleming died less than one month before Ian). She describes the Flemings sifting through Eve’s goods, eldest first, but finishes the portrait with a sad and arresting illustration,

‘Peter Fleming gazed as one on a mountain in Tibet, puffing his pipe and nary a glance at his relations.’ (p.362 Amory)

Forever consumed by his travels, forever eschewing ennui or suffering with escapism. There is real deference to Peter as patriarch of the Flemings, evident when Ann, though vehemently against the Bond continuation series that Kingsley Amis was about to commence, notes ‘since Peter Fleming agrees to the counterfeit Bond, I am prepared to accept his judgement. Though my distaste for the project is in no way altered.’ (p.383 Amory) Ann valued, respected, and accepted Peter’s opinion, just as the other Flemings had done so.

Having established himself as an impressive adventurer and explorer, a military leader in time of war, and a proficient editor and writer long after his days with the Eton College Chronicle, Peter Fleming became the best-selling author of 19 books. These achievements should not be forgotten. He thrived as a writer, as a traveller, as a soldier, and as a spy.

*

On August 18th 1971, Peter shot a brace of pheasants then collapsed and died after suffering a heart attack whilst on a shooting holiday near the Black Rock in Scotland. Characteristically, Peter had prepared for this event and had written a set of ten instructions regarding his funeral arrangements four years ahead of his untimely death. Requests from the list include having his dog present at the funeral; that his coffin be made from the wood from the estate; for any estate workers who attended or helped with the funeral ‘to be given a good, strong drink when it is over’; and for there to be ‘no mourning’. Along with these instructions was an epitaph, a draft form of which still exists in the Peter Fleming Papers at Reading University Library.

To understand the man that fashioned himself as a writer, traveller, and soldier, then we need look no further than to the self-composed epitaph that consolidates all that Peter was and how he wished to be remembered:

He travelled widely in far places;

Wrote, and was widely read.

Soldiered, saw some of danger’s faces,

Came home to Nettlebed.

The squire lies here, his journeys ended –

Dust, and a name on a stone –

Content, amid the lands he tended,

To keep this rendezvous alone.

R.P.F

Bibliography

Fleming, Peter, Brazilian Adventure, Jonathan Cape, (London, 1933)

Fleming, Peter, One’s Company, Jonathan Cape, (London, 1943)

Fleming, Peter, The Sixth Column, Rupert Hart-Davis (London, 1951)

Fleming, Peter, My Aunt’s Rhinoceros, Rupert Hart-Davis, (London, 1956)

Fleming, Peter, Invasion 1940, Rupert Hart-Davis, (London, 1957)

Fleming, Peter, With the Guards to Mexico! Rupert Hart-Davis (London, 1957)

Fleming, Peter, The Gower Street Poltergeist, Rupert Hart-Davis, (London, 1958)

Fleming, Peter, The Siege at Peking, Arrow Books (London, 1959)

Lycett, Andrew, Ian Fleming, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, (London, 1995)

Hart-Davis, Duff, Peter Fleming, OUP, (Oxford, 1987)

Ed., Amory, Mark, The Letters of Ann Fleming, Collins Harvill, (London, 1985)

MS 1391 J/13, Peter Fleming Papers, The University of Reading Library

Incidental Intelligence

Danielle Shaw is a biographer who has written and published on numerous twentieth-century lives. She is currently completing a PhD on sixteenth-century soldier-spies. She works in the School of History at the University of East Anglia and lives in Norwich.

Remembering Ian and Caspar Fleming on August 12

To Peking: A Forgotten Journey from Moscow to Manchuria

The parallel lives of Peter and Ian Fleming (Bond Memes)