Today marks a very special day, for on this day in 1957 Ian Fleming met a young illustrator that was to prove pivotal in the lives of both men and the future of the James Bond novels. That illustrator was Richard Wasey Chopping.

We spoke to one of Chopping’s trustees – Jon Lys Turner – who recently published ‘The Visitor’s Book’ a biography about the lives of Chopping and his life-long partner, fellow artist Denis Wirth-Miller. In our most significant interview to date, Jon provides brand new information about the relationship between Fleming and Chopping and more.

What were your motivations to write this book and take on the responsibility of two men’s legacy?

Photo: The Jon Lys Turner Archive

I was a co-beneficiary of the estates of both RWC and DW-M. I had been a close friend of both for 30 years having been taught by Dicky at the Royal College of Art.

After their deaths, on entering their discarded studios at the end of their courtyard garden, amongst the dust and grime and cobwebs, I was astounded to realise that the amount of their hoard was far greater than I had remembered: pile upon pile of papers, canvases, sketchbooks etc. It clearly suggested that the materials were so plentiful that this was potentially an archive. This absolutely fascinated me. I had no idea how thorough they had been with keeping materials (although it may well be they had simply put it all out of their minds).

A director of the Tate visited the studio with us and told us this was important – maybe one of the most significant post-war archives to be discovered in decades. The materials came to me in the agreement with my co-beneficiary. A few more Tate academics looked at the materials (then with me in London – now in a bank vault). I was asked if I would put together the bones of a catalogue for a potential show of the archive. I explained that I am not a writer – I am a creative director – but agreed to try.

I sorted papers chronologically and filed correspondence from key friends and acquaintances in one place. The dates ranged from 1936 to 2008. Even phone bills tell a story (ie how often they spoke to Francis Bacon – often twice a day). The whole project lasted about 4 years due to the size of the archive (my agent Clare Conville calls it “an embarrassment of riches”).

I researched and researched and researched. I started to recognise initials at the bottom of letters and I found myself warming to certain characters and recognising their handwriting as soon as I saw an envelope covered in their script. I interviewed many people – allowing me to meet some wonderful, colourful characters who could directly answer some of the unsolved questions. This exercise continued to grow. It was soon far more than just a potential catalogue. Representatives of The Estate of Francis Bacon, when visiting me, suggested that my project should become a book.

The most important find was a box containing Dicky’s writings for his desired autobiography. This had been rejected multiple times by publishers . (He was furious to find a note written on his returned manuscript reading:“poetic at times, but I just can’t see people wanting to read this account of his not very interesting parents & family”). I realised that as a creative director, I might just have an understanding of a contemporary literary ‘appetite’ for the D+D story. I could possibly work Dicky’s memories into something very different by blending in many of the other documents and diary extracts etc that would create a very different kind of biography appealing to contemporary readers. I always make sure I explain that I am not an academic or a historian – nor do I strive to be.

It has always been important for me to reflect the strength, grit and honesty with which they had lived their lives. They were living against the law as a gay couple (Denis was imprisoned in 1944 for gross indecency and Dicky had to move and hide after News of the World hounded them).

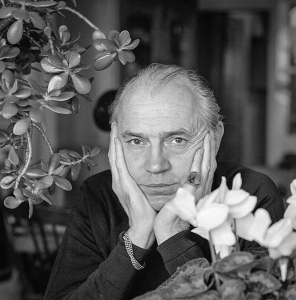

Richard Chopping – 11-10-1971 © Edward Morgan

So, a biography: I grappled with this. Dicky had asked me to accept the role as his literary executor. He wanted his memories to be shared and he feared Denis would destroy any physical materials. Dicky would leave swathes of material with me when he stayed with me in London. Their behaviour was sometimes so bad that a thorough intimate rendition of their lives might not do justice to their memory. But overall I was utterly determined that the lives of these two amazing characters should go unrecorded.

I started by setting myself two guidelines: firstly this wasn’t about me and secondly that this shouldn’t be about Bacon. The title alone of my book will tell you that I didn’t win the latter (it was explained to me that the book would hardly get noticed if it was just about D+D and probably wouldn’t even get published).

I don’t lay any claim to the legacy of Chopping and Wirth-Miller although I do get hot under the collar when – due to my book – they are flippantly dismissed as minor artists or just ‘gay interest’ in the press within the context of Bacon or Fleming. I hope simply to have been a recorder of what I inherited, melded with my 30 year experience and my first hand anecdotes from D+D as well as much information from interviewees.

Much of the archive of correspondence between the Fleming and Chopping between 1957 and 1966 was sold at auction in New York in 2010 selling for $57,600. Chopping felt swindled having trusted an American dealer to whom he sold these articles for a fraction of that cost a short while earlier. (all letters retained)

I found one handwritten diary/book in Dicky’s archive which lists in chronological order all his works for Fleming, including notes of the personal dedications that Fleming had inscribed when gifting him with a first addition. Chopping’s final insertion on this timeline simply and coldly states “1966 – Dead,” followed by a household note to himself, “remember to put the clock’s back.” !

Much has been made of the financial grievances that Chopping felt towards Fleming in various press articles, so can you shed more light on how Dicky really felt?

Dicky could easily be stirred up in his later years on the subject of his Bond covers after countless people would tell him that he’d be mega-rich if he’d held copyright. Eventually he would roll off the standard, waspish reply about having been ‘cheated’. I have found that many well-known people repeated a similar response ‘off pat’ to standard questions – particularly when that response has been well received initially. Dicky knew that his copyright “swizz” (his word) was always well received. A “swizz” really wasn’t the case though – as Dicky told me and as the archive shows.

In sensible conversations about the topic between the two of us he told me far more interesting stories about his encounters with Ian Fleming. He explained how generous Fleming had been, how complicated the copyright law was at the time between illustration, ‘commercial art’ and painting.

In one of the letters in Fergus Fleming’s book [‘The Man with the Golden Typewriter‘] Ian Fleming talks of offering to quadruple RWC’s fee. Dicky also attempted to find further royalties for him, and surrendered any claims of copyright to the cover images.

If he had a criticism of Fleming it was that he found that Fleming was over enthusiastic and threw ideas at him left right and centre (“asking for everything in the picture including the kitchen sink”). Dicky would work to persuade IF to pull back a bit from these multiple requests – explaining what we’d now call the “less is more” thought. But it’s a far better client who gives a commercial artist such a clear brief and Fleming’s enthusiasm and determination to be involved in his covers was a very positive force even if challenging.

8 of the original Bond novel Jackets by Richard Chopping / Chopping photo: http://www.007magazine.co.uk

Fleming wasn’t one of those clients who sees the finished article and wants multiple changes due to not having conveyed his brief succinctly. IF loved Dicky’s work. IF knew what he wanted and he explained it clearly. Dicky understood IF well and he delivered according to IF’s brief (albeit rather too slowly at times for IF: one of Dicky’s greatest frustrations was with himself – at his lack of speed in producing an artwork). His detailed trompe l’oeil style was so time-consuming and IF was ecstatic when he received the artwork. To me that is a perfect client/commercial artist relationship. And the financial commission was good.

Dicky’s trompe-l’oeil process was time-consuming and his attention to detail did not lessen for commercial commissions. He held Fleming in high regard. If he delivered, he knew he would be kept on board for future Bond titles, and the series was growing even more popular; Fleming’s satisfaction looked like it would ensure him a decent living.

In the knowledge that he was unlikely to be involved in any other enterprise that made so much money, Chopping asked whether he could keep the copyright to his covers. Fleming agreed. Chopping then asked if he could waive his fee in exchange for a small royalty: ‘Where upon, as rapidly as a shot from a Smith & Wesson, he said, “Oh no, my company wouldn’t wear that.”’ Nonetheless, the amount of money he received from Fleming dwarfed that received from other commissions, and it gave him the freedom to pick and choose other projects.

Ian Fleming (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Dicky’s first cover picture was sold to Fleming at fifty guineas in 1957. On 20th July 1960, Fleming asked Chopping if he would illustrate his next book for 200 guineas, which was an extremely generous fee for the time, “the title of the book will be Thunderball. It is immensely long, immensely dull and only your jacket can save it!” The first print run was 50,938 copies. As Bond’s popularity soared, Chopping tried for a royalty on each book, but his request was flatly denied. So as the only alternative he would increase his fee when possible. He really felt at last he was about to agree a separate American fee from Fleming when the author’s failing health made Dicky lose his bottle about asking. By 1965, the year after Fleming’s death, when Chopping did a painting for the cover of ‘Octopussy’ And ‘The Living Daylights’, his fee had increased to 350 guineas.

Anthony Lejeune writing in The Tablet 20th April 2002 (an article cut out and saved by Chopping) wrote, “Fleming paid out of his own pocket to Richard Chopping for the superb rose-and-gun jacket of From Russia with Love; after which book sales soared like the Moonraker rocket. It was a typical move. He went to the best craftsman and got the best result.”

On another occasion IF enthused: ‘no one in the history of thrillers has had such a totally brilliant artistic collaborator!’

In fact based on the success of Bond covers Edward Pond, the founder of Paperchase, considered in 1966 the production of a series of Bond wallpapers for Central Studio of Piccadilly using artwork from Dicky’s covers but it was decided that wallpaper would not suit Bond’s public image. Pond then requested the possibility of using some of Chopping’s plant drawings for wallpaper instead, an option also declined by Chopping.

Alongside saving the physical still-life objects of the Bond jackets, Chopping also amassed torn sheets all ripped from newspapers and colour supplement magazines of guns, brightly coloured flowers and roses, dragonflies, flies, wood grain and knives, all of which have been kept and can be pieced together to see from where the exact inspiration was extracted. Reference: “The skull was given to me by Dr Kershaw”.

Did Denis Wirth-Miller assist Dicky with any of his Bond paintings such as For Your Eyes Only?

Dicky credits Denis with having played a role in the designing of the Bond covers. Denis watched Dicky mulling over ideas for ‘For Your Eyes Only’, seemingly getting nowhere with the suggestions he was pitching to Fleming, so Denis suggested that Dicky use his recognised trompe l’oeil style with the subject matter being a hole smoothly bored out of a piece of an old, grained, grey-bleached wood with one spooky light blue eye staring at the reader with the author’s name scripted onto a brass drawer plaque. When mocked up Fleming loved it and so it went ahead.

Dicky credits Denis with having played a role in the designing of the Bond covers. Denis watched Dicky mulling over ideas for ‘For Your Eyes Only’, seemingly getting nowhere with the suggestions he was pitching to Fleming, so Denis suggested that Dicky use his recognised trompe l’oeil style with the subject matter being a hole smoothly bored out of a piece of an old, grained, grey-bleached wood with one spooky light blue eye staring at the reader with the author’s name scripted onto a brass drawer plaque. When mocked up Fleming loved it and so it went ahead.

When the subject of type was addressed, Dicky accepted that he had no experience of typography. This was a recurring issue with his book jacket work. He spent several days in his studio attempting to design an appropriate font. Wirth-Miller came to his assistance and offered a solution: an ornate or a simply fashionable typeface would have been inappropriate for a Bond novel, it needed something more masculine. He should use a basic, utilitarian font Denis suggested that Dicky should look at typefaces used by the army, such as the one stenciled onto ammunition boxes and vehicles.

This same type was used on the wood of tea chests (an ammunition case and old tea chests were found in Chopping’s studio and may have been the influence). Chopping discovered that the font was called ‘Packing Case’, which he was easily able to apply in capitals with great visual effect. It became part of the Bond brand.

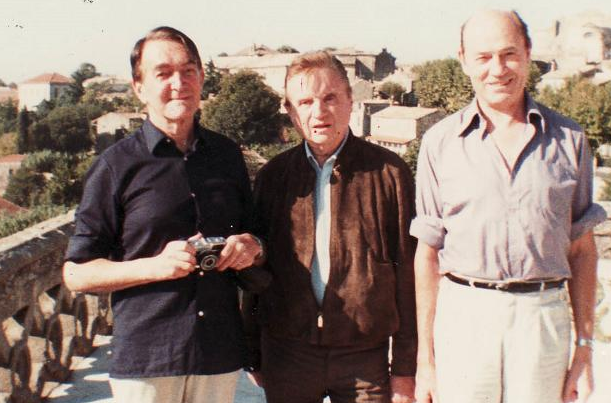

Photo: The Jon Lys Turner Archive

Did Dicky have a favourite Bond painting of his own?

I’m afraid that I don’t know the answer to this but when he sold most of his Bond materials Dicky retained many proofs, photos and original drawings for ‘Goldfinger’ and a few for ‘Thunderball’ which suggests that he favoured these.

Photo Copyright: The Jon Lys Turner Archive

Who were some of Dicky’s favourite artists and how did he come to favour the Trompe l’oeil style?

Chopping’s interest in trompe l’oeil led to his work being included in an exhibition called The Eye Deceived mounted at the Graves Art Gallery (a public gallery in Sheffield which had opened in 1934 under the stewardship of John Rothenstein before he moved to the Tate.) Chopping’s works were titled Pansies and Snails, Pears and Still Life. Dicky’s diary shows his interest in some of the other trompe l’oeil artists included in the show: Carlo Crivelli, Grinling Gibbons, William Harnett, Edwin Lutyens and Stanley Spencer.

Other contemporaries he admired were their great friends The Two Roberts (Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde), John Nash (his mentor from Wormingford), John Lessore (whose mother ran the Beaux Arts gallery) and another great friend John Minton.

What are some of your favourite paintings by Dicky, Bond or otherwise?

I have always loved Dicky’s early paintings (war-time) – he would use his beautifully crafted traditional skills to deliver mundane subjects in a challenging, unexpected manner – such as his 1940’s series of traditional family scenes with a group usually seated around a kitchen table, where his eye would have scrutinized each creature before representing them with the most characterful, amusing, cruel, or sometimes just grotesque features.

Photo Copyright: The Jon Lys Turner Archive

Dicky was also a published author including The Ring and The Fly. Did he plan to publish anything else and could we ever read more of his written work?

His first novel ‘The Fly’ was eventually published over a decade after its conception (because it was considered too outrageous for years) in 1965, thanks to the mentorship of Angus Wilson who introduced the publishers Secker & Warburg, where David Farrar described it as, “a perfectly disgusting concoction.”

The book was edited by Giles Gordon, who later wrote that he was determined to like the novel, hoping that “more no doubt better books would follow, but ‘The Fly’ was indeed disgusting.” according to Gordon due to Chopping being “most fastidious” and his book being sufficiently sordid to appeal to voyeurs, and once adorned with one of his famous dust-jackets became “a succès de scandale.” The Sunday Citizen called it “Just about the most unpleasant book of the year, but it held me like a fly in a spider’s web of monstrous cruelty.”

On the back of this success Chopping was offer a deal for second novel which appeared two years later entitled ‘The Ring’. Gordon reminisced; “Chopping’s second novel, and mercifully the last to be published, The Ring, albeit embellished with a revoltingly clever cover, was a much more mundane affair than The Fly and sank with very little trace.”

Chopping did have a few more published works including his part in the 1967 Hodder and Stoughton ‘Lie Ten Nights Awake’ which included a story by Anthony Burgess of ‘Clockwork Orange’ fame. Dicky’s tale involves rambling strangers being given unexpected hospitality in the wilds of a remote mountainscape and fed by an extraordinary family whose ultra-handsome son is a taxidermist. The outcome of the story is that the stew was in fact made of the meat from their unfortunate grandfather who was just being stuffed.

Chopping did have a few more published works including his part in the 1967 Hodder and Stoughton ‘Lie Ten Nights Awake’ which included a story by Anthony Burgess of ‘Clockwork Orange’ fame. Dicky’s tale involves rambling strangers being given unexpected hospitality in the wilds of a remote mountainscape and fed by an extraordinary family whose ultra-handsome son is a taxidermist. The outcome of the story is that the stew was in fact made of the meat from their unfortunate grandfather who was just being stuffed.

Dicky’s long-term friendship with, and admiration of, Stephen Spender had endured since 1939 and it was with Spender’s help as a Board Associate of the published writer’s retreat Hawthornden Castle that Dicky was able to attend in the mid Eighties. Dicky had decided to rewrite a contemporary version of The Fly. The Castle was owned by Mrs Heinz of the American Heinz grocery product family (or ‘Mrs Beans’ as DW-M referred to her)

The setting was romantic. But when out of the grounds Dicky was not so positive; “Rosewell is one of the last places God made and He forgot to finish it. The village butcher looks like the Scots cousin of Sweeney Todd and there is the most dismal and depressing pubs I have ever seen.” His cruel observational skills were of course able to propagate in a perfectly conducive climate; “There is a strange young man with a face like a boiled potato.”

Even at this time (late 1980s) the other writers in residence were still stirring him up about the deal with Fleming until it was gnawing away at him, but justifiably he was especially angry at the inability to reproduce his own artwork. When Denis wrote a letter to the Castle he mentioned the news about a possible new copyright law and Chopping responded that it “sounds as if it goes through I shall a last get the right to reproduce the covers.”

Outside of the bohemian art world, what were their interests?

They travelled – adoring France, they liked walking, they took photos. Dicky kept sketchbooks and many note books full of written observations of the trivia of other people’s lives. Dicky was obsessed with literature and read like crazy (long term member and supporter of The London Library) and he had a huge collection of classical and operatic CDs. Denis gambled and was very good at it and he learnt to speak French – twice spending months in the South of France at a language school – till Bacon arrived and dragged him to a casino with champagne!

They saw most major art exhibitions. They travelled with Bacon to all his international openings. Dicky volunteered as a Samaritan in Colchester. Dicky taught at the RCA and would spend time with ex students helping with theatre and film projects.

Photo Copyright: The Jon Lys Turner Archive

What kind of legacy do you think they would have wanted?

Denis claimed that he couldn’t care less about any form of legacy – this I think was defensive. Dicky still enjoyed the glow of being successful and wanted his name and work remembered.

Do you plan to publish any further materials about them or would like to?

Yes – but very different from The Visitors’ Book. There is also a potential TV film of TVB so fingers crossed.

Incidental Intelligence

Jon Lys Turner is a creative director and has worked at the top end of the UK design industry ever since completing his Masters degree at the Royal College of Art, and has been creative director to some of the world’s largest brands.

Jon Lys Turner is a creative director and has worked at the top end of the UK design industry ever since completing his Masters degree at the Royal College of Art, and has been creative director to some of the world’s largest brands.

Jon was also recently featured in the BBC Fake or Fortune programme, which set out to investigate whether a painting given to Jon by Richard and Denis allegedly painted by Lucien Freud was indeed, real or a fake. He lives in London.

The Visitors’ Book: In Francis Bacon’s Shadow: The Lives of Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller (Constable, London) by Jon Lys Turner reveals a wealth of new, truly staggering biographical information from the archives of the artists Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller.

With an extraordinary supporting cast including Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, this is the untold story of two of the most fascinating figures to emerge from the turbulent world of post-war British art. Successful artists, although not household names themselves, writing Dicky and Denis off as just footnotes in history would be a mistake. This biography is a tale of transgression, hedonism and innovative talent. With reams of previously unseen material, this book offers a fascinating and unique delve into post-war Britain.

With an extraordinary supporting cast including Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, this is the untold story of two of the most fascinating figures to emerge from the turbulent world of post-war British art. Successful artists, although not household names themselves, writing Dicky and Denis off as just footnotes in history would be a mistake. This biography is a tale of transgression, hedonism and innovative talent. With reams of previously unseen material, this book offers a fascinating and unique delve into post-war Britain.

Buy ‘The Visitor’s Book‘.

Visit Jon’s website and follow on Twitter.

What a great interview.

As somebody who finds cover art and design endlessly fascinating I think that the late greats: Chopping and Raymond Hawkey are in an absolute league of their own and I find it so interesting that they both did Bond.

I bet Le Carre would have loved to have found this level of artistic excellence for his works.